Lily hated her painting. Sitting out in the Ramsay family yard, easel propped in the grass overlooking the sea, Lily doubted her impulse to paint in the first place. She worried someone might wander by, peer over her shoulder, and look at her work. Might look at her pushing around shapes and forms, grasping at some unrealized composition so clear in her mind’s eye. How to make something of the scene in front of her? Something from the bright violet flowers and the hard, white walls.

“She could see it all so clearly, so commandingly, when she looked: it was when she took her brush in hand that the whole thing changed,” Virginia Woolf wrote of Lily in her novel, To the Lighthouse. “It was in this moment’s flight when the demons set on her who often brought her to the verge of tears and made this passage from conception to work as dreadful as any down a dark passage for a child.”

The book was self-published in 1927 by Virginia and her husband’s printing press, Hogarth. Their logo, a snarling wolf, was made of a woodcut by Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell. Like Lily, Vanessa was a painter. She painted in the bold and fashionable Post-Impressionist style on canvas and on the walls of her home. She painted alongside her partner in life and sometimes love, Duncan Grant. The two lived a life wrapped completely in color. “Whenever Duncan and Vanessa entered a house there was a fifty-fifty chance they would cover the walls with decoration,” wrote Vanessa’s son, Quintin.

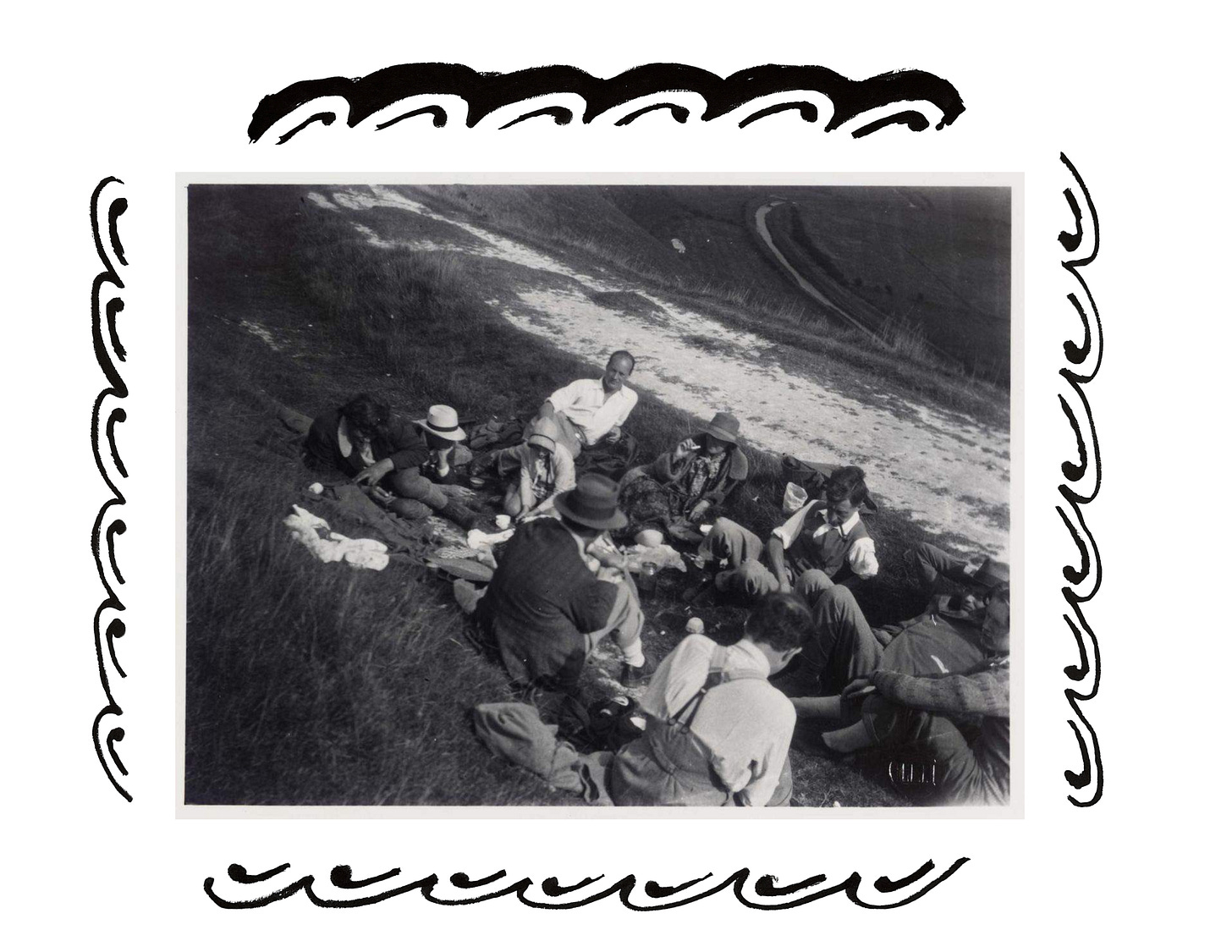

In To the Lighthouse, Virginia tells of a family and friends vacation on the Scottish coast, a coast that Virginia and Vanessa’s family – the Stephens – visited growing up. The novel’s point of view spills from one character’s interior life to another’s, with the most attention pooling in the mind of Lily the painter. They experience that mix of ease and melancholy that occurs on vacation. The descriptions, mostly coming from Lily, depict the shapes and views of the natural world around them. Perhaps this came from Virginia’s closeness to her sister and her insistence on the forms of things; their different ways of seeing the world one of the throughlines of their lives.

So Virginia was concerned with depicting interior life, Vanessa concerned with interiors. In a speech for a local school, Vanessa wrote that she felt writers, her sister included, did not see things for how they really were. Objects are noticed for what they stand for, not what they are. A red strawberry means ripeness, an old woman’s grey hair means old age. They don’t see the rich red of the fruit or the salted, tangled strands. Which way is the right way to see?

“It was as if the water floated off and set sailing thoughts which had grown stagnant on dry land, and gave to their bodies even some sort of physical relief. First, the pulse of colour flooded the bay with blue, and the heart expanded with it and the body swam, only the next instant to be checked and chilled by the prickly blackness on the ruffled waves. Then, up behind the great black rock, almost every evening spurted irregularly, so that one had to watch for it and it was a delight when it came, a fountain of white water; and then, while one waited for that, one watched, on the pale semicircular beach, wave after eave shedding again and again smoothly, a film of mother pearl.” - Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

Vanessa created beautiful covers for Virginia’s books. At the time, critics and Leonard Woolf alike voiced some dislike of the woodblock printed covers, which they found to be both too childlike and feminine. But Virginia liked them and believed in her sister's vision. Today, they feel remarkably fresh; unique and loose, childlike yet still controlled.

The sisters belonged to what is known as the Bloomsbury Group. What began as casual Friday dinners of Virginia and Vanessa’s older brother Thoby’s Cambridge friends, evolved into the famed circle of artists, writers, and thinkers living in early 20th-century London. Bohemians of sorts, hunched around tables, sharing ideas and itches that might allow them to escape from the stuffiness of Victorian society. “When I talk of members, I do not mean that there was any sort of club or society,” wrote Vanessa Bell of the time. “Yet people were definitely ‘Bloomsbury’ or not and this is a convenient way of classifying them.” Despite her sister’s more prominent posthumous fame, it was Vanessa who was known as the “Queen Bee of Bloomsbury.”

There’s something inherently fascinating, almost mystical, about this idea of a creative group. In the Bloomsbury group’s case, some of this mysticism might have come from their alluring name. Vanessa acknowledged, having witnessed the widespread interest around her life’s group in her old age: “It is lucky perhaps that Bloomsbury has a pleasant reverberating sound, suggesting old-fashioned gardens and out-of-the-way walks and squares; otherwise how could one bear it? If every review, every talk on the radio, every biography, every memoir of the last fifty years, were to talk instead incessantly of Hoxton or Brixton, surely our nerves would be unbearably frayed.”

Or perhaps this sense of mysticism came from its burying under history, and the layers of dust that settled into the story’s grooves. Dust makes for interesting shapes, as Vanessa herself knew. She once scolded her housekeeper for dusting the corner of her studio, wanting to preserve it to reference in her still-life painting.

And then there’s that Charleston House.

Tucked away in Sussex County, only a short train ride into the countryside, the Charleston House was a space of refuge for Vanessa Bell, her two sons, Duncan Grant, Duncan’s lover, and any other Bloomsbury friend who might want to come by for some fresh garden air. They retreated there during the First World War at the suggestion of Virginia, who lived in another country home nearby, then used it as a summer home and then again as a full-time home. “The house was large enough for family friends, unpretentious and congenial, and although remote, easily accessible,” wrote Vanessa and Duncan’s daughter, Angelica, who was born after moving into the house. “Vanessa, marveling at the beauty of the light on the flint and brick walls, was seduced by the apparently unlimited possibility of freedom.”

I wonder if it’s this sense of freedom that shines through the interiors that makes the Charleston House so exciting to look at. The decorations on the walls were “carried out rapidly and without due preparation,” as Vanessa’s granddaughter wrote. The house was leased, and therefore “permanency not the most important consideration.” Only the urgency of the moment, and the opportunity of all that white. Maybe, unlike Virginia’s Lily, Vanessa did not fear the white. This is the paradox of the blank slate – it breeds either opportunity or anxiety, sometimes both.

“The two sisters were trained in two very different disciplines and, although united by an affection which was very strong, they were divided by their very different perceptions of the arts. Virginia would refer to Vanessa’s ‘strange silent fish world’ and although Vanessa found Virginia’s description of the Stephen family at St Ivens in To the Lighthouse almost unbearably moving she could, also, as Virginia herself despairingly recorded, ridicule her taste in green paint.” - Quintin Bell, Charleston: A Home and Garden

Vanessa and Duncan’s artwork radiated across the home, inching its way up the walls, across tables, and along the outside of the bathtub. Nothing was opaque, paint wasn’t filled in completely. They left the brushstrokes visible, preserving their learned looseness of hand. They pulled imagery from antiquity, painting naked nymphs with generous curves, lute-playing figures, footed pottery, and the swirled edges of Ionic columns. Duncan returned to these romantic motifs over and over in his work, whereas Vanessa used them only in her decorative work.

A dining table design faded with use, only to be painted over again. Still lifes were staged, and friends posed for portraits against those painted walls, creating layered works. Vanessa and Duncan relied on inexpensive chalk-based paints for their decor, which produced a fresco-like look, imbuing the walls with the quiet prestige of a church mixed with the worn humility of a nook. They painted simplified forms of flower arrangements, and painted patterned borders on seemingly all the furniture. Anything could be a frame. They added cross hatches to the edges of their objects, as if gesturing at the three-dimensional form of things with the reminder that it was still painted, was just pretend, like a theater set.

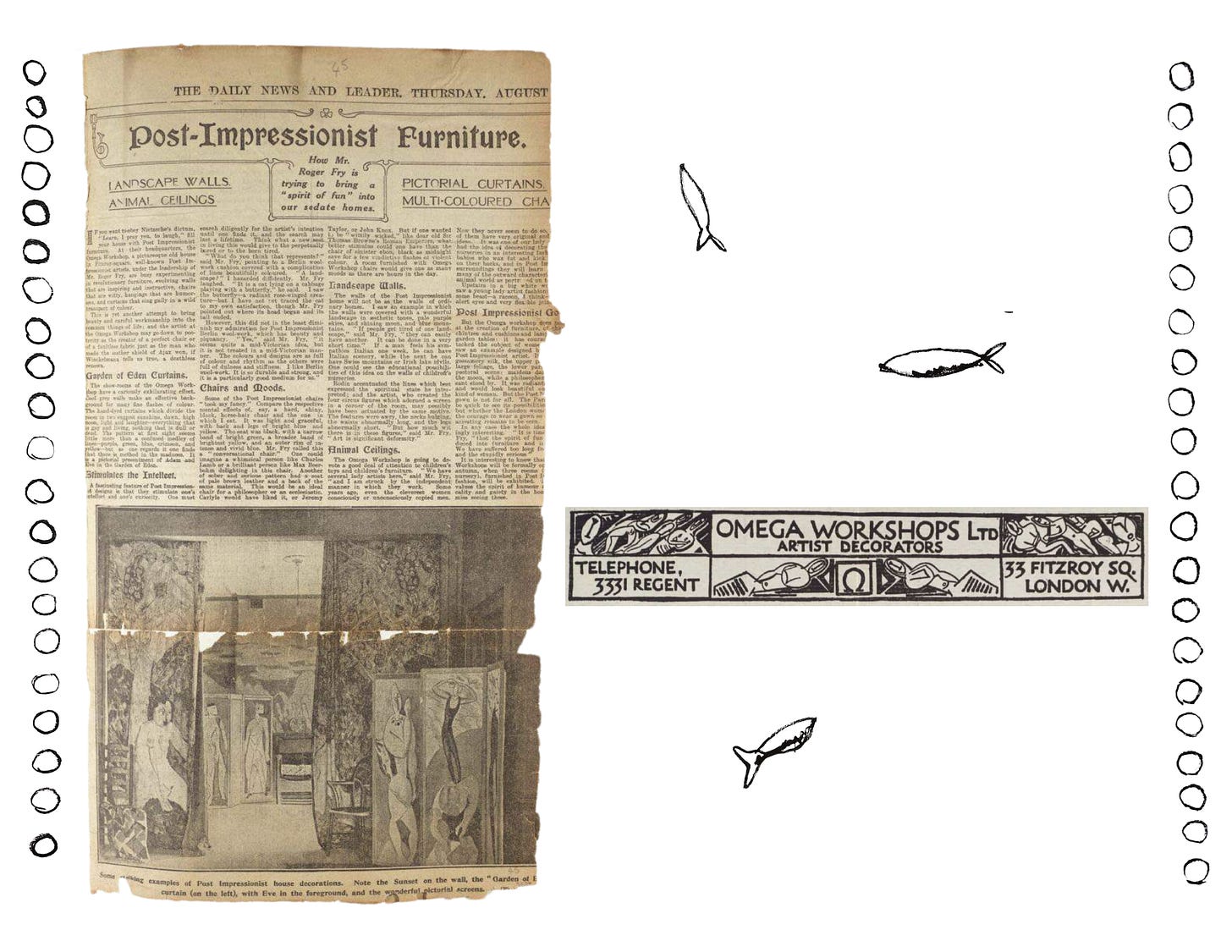

Much of their textiles came from the work they produced for the Omega workshop, a design company started by fellow Bloomsbury member Roger Fry in 1913 as a way for artists to financially support themselves and to minimize what they believed to be the false distinction between fine art and “domestic decoration.” Vanessa and Duncan were highly involved, turning out painted furniture, textiles, pottery, carpets, and even clothing. Work was left unsigned except for an omega sign. Despite its success, the Omega Workshop crumbled in the face of war.

“It was odd, she thought, how if one was alone, one leant to inanimate things; trees, streams, flowers; felt they expressed one; felt they became one; felt they knew one, in a sense were one; felt an irrational tenderness thus (she looked at that long stead light) as for oneself.” - Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

The Charleston house evolved with time, wear, and more things made and acquired. Quintin took up pottery and his ceramics filled the rooms. Paintings that Roger Fry had bought, such as an early Picasso, were sold, but not before someone in the house would replicate it and hang the copy in its place. In this way, the interior of the country house evolved as Virginia’s characters evolved. Not necessarily moving towards a perfect version of a home but instead naturally unfurling.

There’s something aspirational about the Charleston House’s blurring of art and daily life. The house itself became art that could be stepped into, curled up against, or eaten on top of, crumbs wiped off of. I’m always yearning for this combination.

Vanessa always had hired help – there were others to cook, others to clean. For her, the house was a space of creativity, not of upkeep. Still, her children diverted her attention away from her work, as Virginia, who had no children, complained of in her journals. Despite personally struggling with domesticity, Virginia found the experience interesting in others. Or could her irritation be the thing that bred such interest? “Virginia Woolf would often probe her friends and relations about even this most trivial aspect of their daily lives and would interrogate them about their breakfast as a way of intense curiosity about people,” wrote Vanessa’s granddaughter, “‘What did you have for breakfast?’ developed into a family joke.”

The Charleston House feels like the life Virginia’s characters gesture at, a total acceptance of life how it is: “One wanted, [Lily] thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience, to feel simply that’s a chair, that’s a table, and yet at the same time, It’s all miracle, it’s an ecstasy.”

Books Referenced:

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Sketches in Pen and Ink: A Bloomsbury Notebook by Vanessa Bell

Charleston: A Bloomsbury House & Garden by Quintin Bell and Virginia Nicholson